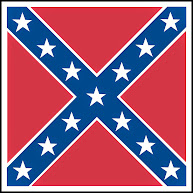

Complicity: How the North Promoted, Prolonged, and Profited From Slavery"

'Complicity' uncovers North's ties to slavery

Slavery in the South has been documented in volumes ranging from exhaustive histories to bestselling novels. But the North’s profit from–indeed, dependence on–slavery has mostly been a shameful and well-kept secret . . . until now.

In this startling and superbly researched new book, three veteran New England journalists de-mythologize the region of America known for tolerance and liberation, revealing a place where thousands of people were held in bondage and slavery was both an economic dynamo and a necessary way of life.

Complicity reveals the cruel truth about the Triangle Trade of molasses, rum, and slaves that lucratively linked the North to the West Indies and Africa; discloses the reality of Northern empires built on profits from rum, cotton, and ivory–and run, in some cases, by abolitionists; and exposes the thousand-acre plantations that existed in towns such as Salem, Connecticut.

Here, too, are eye-opening accounts of the individuals who profited directly from slavery far from the Mason-Dixon line–including Nathaniel Gordon of Maine, the only slave trader sentenced to die in the United States, who even as an inmate of New York’s infamous Tombs prison was supported by a shockingly large percentage of the city; Patty Cannon, whose brutal gang kidnapped free blacks from Northern states and sold them into slavery; and the Philadelphia doctor Samuel Morton, eminent in the nineteenth-century field of “race science,” which purported to prove the inferiority of African-born black people.

A startling new history exposes the plantations, slave ships, and rebellions in the North, upending the notion that slavery was a peculiarly Southern institution.

In 1641, Massachusetts became the first colony to recognize slavery by statute. Four years later, a Boston ship made one of the earliest known slave voyages from New England to Africa.

By the late 1700s, tens of thousands of blacks were living as slaves in the North. "Complicity" shows just how integral slavery was to the region's economy.

The scope of the North's involvement with slavery is staggering to anyone raised with the notion that slavery was limited to the South.

In the mid-1800s, Charles Sumner, a Bay State abolitionist, railed against the unholy alliance "between the cotton-planters and flesh-mongers of Louisiana and Mississippi and the cotton spinners and traffickers of New England -- between the lords of the lash and the lords of the loom." In 1861, the mayor of New York suggested the city -- long a hub of illegal slave trade -- secede from the Union in large part so cotton trade with the South could continue.

"Complicity" grew out of The Hartford Courant's investigation of slavery throughout Connecticut. The reporters discovered that more than 5,000 Africans were enslaved in Connecticut during the year before the American Revolution. Now three Courant veterans have produced a rich history of slavery in the North that adds new dimensions to what you might have learned in school.

The successful voyage of a slave ship was 10 times as profitable as an ordinary trading voyage from New England to the West Indies. Rhode Island entered the slave trade in a big way, shipping nearly 50,000 slaves in less than 20 years. By the mid-18th century, plantations in the Narragansett area matched the plantations of Virginia's Tidewater region in acreage and numbers of slaves.

For more than a century, Ivoryton and Deep River, Conn., were an international center for milling elephant tusks into piano keys. As many as 2 million enslaved Africans carried tusks hundreds of miles to the coast so the tusks could be shipped to America. Two industry leaders were abolitionists who ignored the contradiction between their business and their politics.

"Complicity" joins a number of books published over the past year that have taken a closer look at slavery. "Runaway America: Benjamin Franklin, Slavery, and the American Revolution" by David Waldstreicher analyzes Franklin's history as an indentured servant and, later in life, a slaveholder. "New York Burning: Liberty, Slavery, and Conspiracy in Eighteenth-Century Manhattan" by Jill Lepore examines the fires of New York City in 1741 to which "Complicity" devotes a chapter. The fires were thought to be a slave rebellion and 30 slaves were executed.

Unlike the tighter focus of those two books, "Complicity" ranges across a wide swath of territory and time. This is the book's weakness as well as its strength. Each chapter moves to a new place and another facet of the North's entanglement with slavery. A reader can be forgiven for feeling that this is history for the fast-paced MTV generation.

Yet the sheer volume of numbers and narratives from Northern states brings home the extent to which slavery was a part of everyday life in a region largely defined by its antipathy toward the institution. Much of what's in "Complicity" was gleaned from old newspapers and more than 100 period drawings, photos, and documents bring a sense of immediacy to the storytelling. This is history at its best, a story not only of the government officials who made front-page news, but a story of the fugitive slaves for whom a bounty was offered in the classified ads.

Most Americans learn that slavery was a southern institution, but in fact, many enslaved Africans were held and worked in the North.

Many northern industries and businesses–shipbuilding, ports, banks, insurance companies, textile mills–were dependent on slave labor in both the North and South. Northern consumers were dependent on the products of this slave labor for food, clothing, and amenities like ivory piano keys.

In this video below, you will learn about the significant complicity of the northern states in the slave trade, slave labor, and slave-made products in the history of the United States.

https://youtu.be/hAQnlpLaj30